“Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.” – Warren Buffet

Have you heard the story where the price of a room heater increases from USD 10 to USD 60 every year over a period of six months and goes back to USD 15 immediately after the six-month period? One of our employees talked about this curious phenomenon which he had experienced in his alma-mater in India. The locally made room heater used to sell for USD 10 in July –which is peak summer in India, and as soon as winter arrived, the price of the same room heater shot up to USD 60. The brave ones who had assumed that their bodies could withstand the brittle cold of winter were the ones who were at a loss as this phenomenon used to repeat year after year, even after messages were passed from the sophomores to the freshers every year.

Is It Because of Value?

This example underlines the concept of value – hardly understood and greatly exploited. Value is ‘the fair return or equivalent in goods, services, or money for something exchanged; or the relative worth, utility, or importance of something’. In simple terms, we can define value as a contextual, relative, intangible, and subjective perception of the gain from a product by the customer. Price, on the other hand, is always the monetary amount associated with a product. Value is not the same as price. Price is one of the factors that determine value, along with many other aspects.

Value is complex and confusing, whereas price is simple and straight forward. And most importantly, value is more important to a customer than the price.

Customers do not buy a product because of the price but for the value it delivers.

Customers buy from Walmart not because of the low prices but because it provides them with savings even though it may not provide them with the world’s best products. Customers buy an Apple Phone despite its high price because it is a product of very high quality and is also a badge of honor. There are many elements that drive a customer to buy a product. Bain has listed down all these elements in its famous article 30 Elements of Customer Value where they say that it can be difficult to pin down what customers truly value as it is psychologically complicated.1

Only a few organizations understand what their customers really value about their products and even fewer organizations realize the subtle difference between value and price. The ones that do are the successful practitioners of value-based pricing through which they charge a price that is closer to the perceived value of their products. By doing this, these organizations realize optimum profits and the customers do not feel that they are being ripped off. Stakeholder delight is maximum in this scenario.

For the others, it is always a bitter battle between finding the right balance between perceived value their products deliver and the price they set for their products.

The Balance Between Price and Value

Keeping this in mind, we can classify the relationship between price and value in four zones.

Zone 1 – Low Perceived Value and Low Selling Price. We can call this the commoditization zone. Everyday products such as salt, pulses, or bread loaves are great examples of this. Even basic website development services for building and deploying normal websites are examples of such products. Customer loyalty and profit realization is low in this zone as differentiation is hard to achieve. This zone poses some threats for organizations as their products can quickly be replaced. For example, consider the case of Webflow, an online platform through which simple websites can be built without the need for designers. It has put the jobs of website development firms at risk. This zone is also a great point of entry for new organizations trying to make a mark as customer stickiness is low and organizations do not initially tend to notice a small dip in their revenue. This is the reason why supermarkets use everyday product categories to launch their own home brands. For organizations to succeed, it is important that they move their products out of this zone to other zones listed below.

Zone 2 – Low Perceived Value and High Selling Price. This is the free-fall zone. This is the zone that has the maximum danger as product sales can plummet and customers can go away in search of other viable options from competitors. Ask Netflix. In 2011, convinced that customers were getting Netflix for a bargain, Netflix raised its prices under the assumption only a small number of customers would complain, and that the anger would fade away. But Netflix was wrong as they lost nearly a million customers and its stock price plummeted by over 75 percent in the year that followed. If this can happen to Netflix, it can happen to anyone. If you find your organization in this zone, quickly move away as the ignominy of failure and obsolescence awaits you if you continue too long.2

Zone 3 – High Perceived Value and High Selling Price. This is the exclusivity zone. Have your ever wondered why diamonds, or in words solidified carbon deposits, are worth so much? Or for that matter, why are Armani and Gucci shirts priced so exorbitantly? It is important to understand that the perception of the value of a product is not because of the output, but because of the inputs that are used to make the products. Diamonds are extracted after a long-drawn process and are rare. Armani and Gucci shirts are made from some of the finest quality material and designed by some of the world’s leading designers. Hence, the perception of value is high, and these brands can set their prices very high. If your organization is in this zone, play safe and do not try to change, because the profits that you make can make or break an industry. If you still have doubts, ask Apple – most of their phones have a great value perception and are priced several hundreds of dollars above similar products in the market.

Zone 4 – High Perceived Value and Low Selling Price. This is a zone of squandered opportunity. It is a great zone to be in if you are a customer because you are getting a great deal at a price that is a steal. But this is a zone of great loss for organizations because they are leaving too much money on the table. The typical symptoms of organizations that have products in this zone are extremely high customer delight scores and quick stockouts. For example, the Broadway hit ‘Hamilton’ which has won the Grammy award and the Pulitzer Prize faced a similar problem a few years earlier as its tickets, priced upwards of $549 and $139 used to run out in a few hours because it was supposedly far less than what the customers were willing to pay. This created an amazing opportunity for scalpers who earned more than $60 million in 2016. Even though the producers of the show raised the price a few years later, many felt that it was still low. This is a cardinal sin as organizations are not capturing the optimum value for all the stakeholders, especially their shareholders and employees. If you find your organization in this zone, consider yourself lucky that you have a product that customers love and take incremental steps towards moving closer to zone 3.3

The goal for organizations is to find the right balance, and many seldom achieve that. They will continue to move towards the right side and upper half of the quadrant as customers will push for a move towards the left side and lower half. And in the end, we might reach a state of equilibrium.

How Value Changes – CRISP and PACE

The problem that most organizations face in their quest towards finding the zone of equilibrium is their inability to adjust their prices in real time as the perceived value changes.

Why does value change? It is because it is CRISP. And it changes because of four factors that we can term PACE – perception, availability, context, and experience.

Perception

Many argue that perception is reality. But is it? Perception is not just how customers think, feel, and understand about a product, it is also about how customers value the product. Perceptions can change over a period, or from place to place, or from customer to customer. It can also change because of a particular incident.

For example, customers perceive clothes at a retail store to be a low-quality brand if clothes are displayed on crowded racks or hung in plastic hangers in a haphazard way, but the same clothes, hung by a different retailer, will give the perception of a high-end brand, if the clothes are arranged in an ordered fashion with lots of space in between. In the second case, customers will be open to paying a lot more as the value they perceive will be higher. And both can be wrong. The clothing brand may lie somewhere in between being a high-end brand and a low-end brand.

Let us take another example. Johnson & Johnson was one of the most loved brands in the world, especially because of one of its iconic products – baby powder. But, after a set of documents revealed that the company was using talc which could potentially cause cancer, customers started to move away from the brand as the perception turned negative.4

Organizations need to understand this fact that perceptions can change, which in turn can change the value of their products. They need to plan for this and be agile enough to adopt this in their overall pricing strategy. They also need to be ready to accept that in some cases, perception cannot be changed, and the organization will have to work around the changed perception.

Availability

In the book Indivisible: Restoring Family, Faith, and Freedom Before It’s Too Late writes

Economic value is in the eye of the beholder; but the beholder’s eye can be fickle. If you’re taking a cross-country road trip, find yourself desperately hungry, and come to a gas station with the sign out front that says, LAST FOOD AND GAS FOR 120 MILES, you’ll be glad to see a Subway store attached to it. You will value that toasted, foot-long, double-meat club on honey wheat a lot more in that situation than if you were walking around downtown Seattle, where there is a Subway on every third corner.

Availability is the fundamental reason that decides the price of an item. It forms the foundation of economics – demand and supply. It forms the basis for the most popular pricing strategy of recent times – dynamic pricing. It also decides how customers value a product and how its value changes over a period.

Availability of most products fluctuates over a period, either due to environmental factors such as climate or due to other factors such as decline in production, or reduction in availability of inputs. If availability of a product goes down, and the demand for a product goes up, prices and in turn the perceived value for the product go up until availability starts rising and the demand starts falling.

The availability of a product, or the perceived lack of availability can determine how customers value a product. It is the reason why e-commerce companies advertise some products as ‘limited quantity’.

Organizations need to understand that while availability of a product is an important criterion in determining its value, there is also a chance that customers will look at alternatives if the availability becomes a constant problem. It is a fine line between availability and value and organizations will have to find the perfect balance to walk the tightrope.

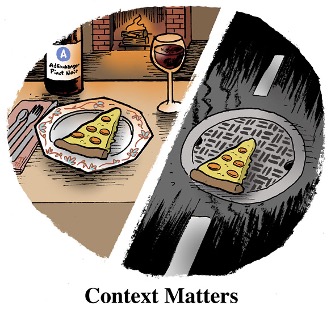

Context

During a hostage crisis in Australia in 2014, Uber raised its prices. Or should we say, Uber’s algorithm raised it? It happened again during concerts and New Year’s Eve across the world. While customers were okay when the prices were raised in the second case, the move to raise the prices by Uber in the first case created a lot of criticism.

Why was this? It was because of the difference in context. Context plays a strong role in determining the value of a product. While customers, after a pint of vodka or wine, are okay with Uber raising its prices on New Years Eve, they are never going to be okay with Uber raising its prices after a terrorist attack. In the case of New Year, customers valued the increased price for the ride as a fair ask for getting them home safely, whereas in the case of terrorist attack, customers felt that the increase in price was not a fair ask when customer safety should have been prioritized.

Context can come from many things. The time of the day, the day of the week, the ongoing season, the locality, and the place the product is sold from, the business and economic environment, and numerous other factors. Even the price that is set, and the price at which a product is sold can be relevant factors that decide the context for a product.

Baseball teams in the Major League Baseball in the US are already practicing this. They are accounting for different contexts such as ongoing rivalries, day of the week, ongoing promotions, record of the team, quality of pitchers, and weather to understand the value that the viewers will give to each game and are setting their price accordingly.5

Organizations cannot consider all the factors that drive the contextual value of a product, nor can they fathom the depths of each of the factors that customers use to determine the value of the product. The best thing that organizations can do is to learn from the past and be prepared and agile enough to adapt to the changes in value.

Experience

Why do the snacks cost a lot in the movie theatres, and sometimes more than the ticket itself? Why does a beer can become so expensive during a ball game and people still buy it? As CBI, a commercial brokerage company points out in their blog, ‘the beer in the game increases in value because you specifically crave a beer at the ball game. That beer has become more significant to you because of the context in which you are drinking that beer. Beer that you have at home is far more common even if it’s the same product. Beer at a ball game is a much more rare and cherished experience, so you are willing to pay the higher price for it.6

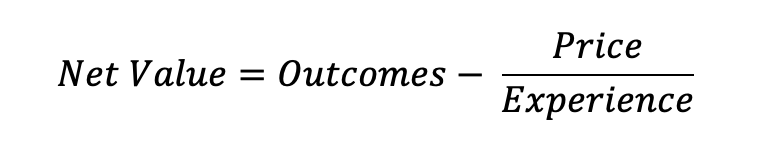

This is the age of experience economy as people today do not buy a product but sign up for an experience and organizations need to understand the relationship between price, value, and experience. Majid Iqbal, the author of Thinking in Services provides a wonderful model which connects all three. He formulates that the net value customers gain is a function of outcomes, price, and value.

Here outcomes are the quantifiable outcomes that customers need, price is the selling price of the product, and experience is the perceived experience by the customer.

This means that if the experience is greater than the price, the net value is higher compared to the scenario in which the perceived experience is lower than the price.

Organizations need to integrate all three and focus on providing a superior customer experience to create superior value for their customers.

The Final Word

Value is difficult – to understand, to measure, and more importantly to master. Organizations rarely get it right and mostly get it wrong. Even when the world is going ga-ga over value-based pricing, many organizations are going in the wrong direction.

They need to understand that the value is CRISP and the value changes because of PACE. Organizations will not always understand how and why customers value a product, but they can realize that the key will not be to master this knowledge but be agile enough to adapt to the evolving changes in value.